Transcript: Russ Ramsey / Rembrandt is in the Wind - Broken People, Beautiful Art, & God.

Russ Ramsey is a pastor in Nashville, Tennessee, and the author of the new book, Rembrandt is in the Wind. Rembrandt Is in the Wind is an invitation to discover some of the world's most celebrated artists and works, while presenting the Gospel of Christ in a way that speaks to the struggles and longings common to the human experience. The book is part art history, part biblical study, part philosophy, and part analysis of the human experience; but it's all story.

In this episode, we talk about broken people, who have made beautiful things, and how those beautiful things lead us back to God.

[00:00:00] Taylor: On today's episode of According to your Purpose, we have Russ Ramsey. Russ is a pastor and author from Nashville, Tennessee, and we got to talk about his new book, Rembrandt is in the Wind. To quote Russ, the book is about beauty, but it's filled with stories of brokenness and how that brokenness leads us back to God. It's an awesome conversation and its an even better book. Here's my talk with Russ.

[00:00:23] Well, Russ, I appreciate you coming on the show. Your book was one of the most fascinating books I have read in a very long time.

[00:00:34] Russ: Thanks for saying that.

[00:00:36] Taylor: You're very welcome. And not to flatter you too much but you're a beautiful writer. And I think for me, so I actually, when I left high school, went to college, I went for art and I got scared and I gave up on that dream and I changed into biology. So full 180. So this book spoke to my heart on a very deep level. So just to set the scene for the people that are listening to this episode, the book is really about, in my opinion, the book is about beauty and brokenness and God, and the connection between these things. So I guess before we get into all that, can you just tell me why art, why should people care? Why should people care about art and beauty and all of these things?

[00:01:21] Russ: Yeah art is a curious subject because it's can be so subjective and yet in any major city in the world, there's a museum that exists just to house things that people have made that have stood for centuries as masterpieces.

[00:01:46] And I'm fascinated by the question of why, like what is it that causes cities and cultures to pour so much into the preservation of these paintings and sculptures that have been fashioned by the hands of people. And it's a very theological thing. When we understand the very opening chapters of the Bible and they talk about the creation of man, in that is a discussion of the nature of God himself. That we're made in the image of God. And the very first thing we learn about God is he makes things he creates. And so then he creates with splendor and glory, and then he makes us in his image, which is unique in all of creation.

[00:02:37] And so when we go about the business of making art, one of the things that we're doing is we're, we are exercising that image bearing quality of his by being sub-creators. By making things of our oww. In this kind of quest to get it something true, get it something beautiful, something that helps explain to us and the world around us why we're here, the significance of being alive.

[00:03:06] And so I've been drawn to art since I was a kid had great art teachers in school who really wanted to develop in us a lifelong affection for the arts and gave us some good guidance for how to go about that. But yeah. Art has just been it's communicated to my soul, not to sound too esoteric, in ways that other things just can't do just by nature of art, being what it is.

[00:03:41] Taylor: I've heard art and music described as the language shared between all people. It's the language of God. And I think that's true. I think what I loved most about your book is that it helped me form a, I've had a lot of ideas throughout the years, broken people or troubled people, or, these troubled geniuses and I've always wondered, like why did they have that touch of spark that these other people don't have. And I couldn't formulate, is the brokenness a part of the genius is the genius. What is it about these people? And I love that your book tied all of these pieces together. It's a coherent worldview about beauty and brokenness and the connection, and really the beauty in brokenness, which is a kind of a unique perspective. So you start this book by telling the story of the statue of David. I wonder if you would mind sharing that story here.

[00:04:39] Russ: Sure. Yeah. The statue of David is in my opinion, I'm gonna say something really ridiculous right now. Like just so -

[00:04:48] Taylor: Go for it.

[00:04:49] Russ: So feel free listeners to prove me wrong. Tell me why I'm wrong about this. Couple caveats before I say the ridiculous thing. I'm not a person who makes lists of the greatest works of art in the world. I'm not somebody who has like favorites. I'm more of a body of work type of person than I am, I like this particular painting or that particular painting. But what I'm about to say has to do with the global reception to Michelangelo's David and the the difficulty of the medium, carving marble, which is in the world of sculpture is the most challenging kind of sculpture because it's an act of pure subtraction. You can't add back to it. So if you make a mistake in the carving away, there's no way to fix it. And so here's the claim. I believe that Michael Angela's David is the single greatest artistic achievement by a human being in the history of the world. That's the claim. It's not my favorite piece of art in the world, but I marvel at it because it's perfect.

[00:05:59] And in ways that I have yet to find a convincing argument for something else to pull ahead of it. And part of it is because he's nude. And so if you're carving a statue and they're clothed it. Overlooks and forgives a lot of potential inaccuracies or mistakes in the carving. But if there is nothing covering the form of the human being, for a human being to look at it, we will notice immediately things that are wrong, things that are off things that are just not the way people really are.

[00:06:42] And to look at Michelangelo's David is to see a as perfect a carving of a human figure with nothing hidden that I can think of. And 500 years of people traveling around the world, giving up their money and vacation days to stand in front of this thing, which has its own room, in the museum.

[00:07:07] So I'm fascinated by the sculpture. And so I wanted to learn about it and learn about how the statue came to be. And it was a really fascinating process because the block from which that statue was carved was actually harvested from the Apuan Alps about 40 years before Michelangelo ever touched it.

[00:07:34] And it was brought to Florence and said in the. Courtyard of the Duomo cathedral with the intention of one day, somebody carving David out of this block. And it would go up on the buttress of the cathedral as one of 12 statues of Old Testament figures that would be up there.

[00:07:53] And two prior sculptors attempted a start. They didn't carve out any of the human figure, but they started, they took the commission and they started working on it. And that led to a hole being carved in the stone, which is where the would run between where the legs are now. And some other chipping away of major areas. But when Michelangelo inherited, when he finally took that contract as a 24 year old was basically a block of marble that had been waiting for somebody to carve David out of it. And he spent about four years carving that statue and. And it was so mesmerizing to the people and so glorious and transcendent that they were like, we can't put this up on the buttress because you won't see it anymore. You'll see a statue of David, but what you really need to be able to do is get up close to this thing and see the perfection of it. And so it ended up being put in the town square, facing Rome, as a kind of a political statement for the people of Florence. They were assuming the posture of David to Rome's Goliath at the time.

[00:09:15] And so that's how that statue came to be. And Michelangelo was a fascinating character because he, even though one of the things he's best known for is the Sistine Chapel ceiling, he hated painting. He thought painting was just beneath him. Two dimensional work just felt like a waste of his time.

[00:09:39] I have a couple quotes in the book about his disdain for the Sistine chapel ceiling project, which is just kind of funny to think about. Because that's what everybody just says "Wow. What a an artist." And he's like I hated that. But the sculpture was his favorite and the challenge of creating something out of a single block of stone was a challenge that he knew in every fiber of his being that he was the best that had ever done that.

[00:10:12] And he was quick to tell people that too. So he was quite a character. But yeah that's how that, that came to be. And it's a fascinating journey that it's been on. And the response, the global response to that particular statue. It tells the story, that people will travel to the other side of the globe just to stand in the same room as it and look at it.

[00:10:38] Taylor: I loved that you included - he was kind of like an athlete or something. When you get - it's almost like reading about presidents. You hear about the best parts of who they were, but then you read their biography and you realize they're just people. And I loved him smack talking other artists. Like " Ohh you're just a painter."

[00:11:00] Russ: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:11:02] Taylor: Fascinating that this guy, who is just so amazing, he's just a kid. He was a kid with ego problems and the problems of wealth and excess and all these different things. He struggled, but yet he was able to create these really amazing things. So at one point in the book you say to get at beauty, we have to get at brokenness. What exactly does that mean?

[00:11:28] Russ: Part of what's happening inside of us when we encounter beauty is there's this longing for something deeper that we feel like we're coming into contact with. And so when you stand at the rim of the grand canyon, for example. People who haven't been to the grand canyon will say "What's the big deal? It's just a big hole in the ground." But when you stand at the rim of the grand canyon, I defy you to say, it's just a big hole in the ground. It's breathtaking and it's something that is - we stand at the edge of a grand canyon because there's something in us that feels like we were meant to stand in the presence of splendor and glory.

[00:12:09] And when we get an opportunity to do that, even in part, we're engaging with something that we believe intuitively, instinctively, is part of what we were made for. CS Lewis famously said that if I find in myself a desire that nothing in this world can satisfy, then the most reasonable explanation is that I was made for another world.

[00:12:37] I love that thought that when we stand in front of glory, it's because we're hungering for something even deeper, something even more perfect, something even more beautiful. It really it's a longing for perfection. To be in the presence of complete unadulterated glory. And that longing that desire in us.

[00:12:57] Is there because we can't just satisfy that in ourselves because we have this brokenness in us. That we're all limited by the brokenness of the world and the brokenness inside of us. And so when we engage with beauty, part of what we're doing is we're arousing an appetite for perfection and that's a perfection that our hearts were made for since the dawn of man.

[00:13:22] And so that's the connection between beauty and brokenness. The beauty is awakening in us, a desire for all that is wrong to be put, and for us to be in the presence of perfect splendor forever.

[00:13:35] Taylor: That was something I had not considered before reading your book. I guess on some deep level, you instinctively know, but I guess what was surprising about it was that for something to be beautiful, it requires the act of another.

[00:13:52] So it's like it, there is no, even if the world existed as it is right now, with beauty all over the place, animals wouldn't be able to participate in that beauty. It requires us as participants in the act of finding something beautiful, which is just a fascinating idea.

[00:14:10] Russ: Yeah. Henri Nouwen in his book The Return of the Prodigal Son, which explores Rembrandt's painting, The Return of the Prodigal Son. He talks about beauty and brokenness and he says, "There is no beauty in brokenness except for the compassionate embrace that surrounds it."

[00:14:28] And so that picture of the prodigal son on his knees and the father's embrace, what's beautiful about that picture is not the brokenness of the prodigal son, but it's that the broken prodigal son is enveloped in the embrace of the father, who is receiving him. And what you were just saying is human beings are unique in this. We're the only ones who think like this. We're the only creature on earth who goes and beholds beauty, for beauty's sake, who wrestles with existential questions about the meaning of life when we stand in front of something that we find to be lovely or beautiful, or we hear a sound that, that stirs us or takes us back. We have a nostalgia for things like this. These are all longings for something transcendent that is a unique quality of human beings that nothing else in creation has.

[00:15:24] Taylor: Speaking of that quote. So that's your opening paragraph of the book. I've never done this before. I read that opening paragraph to both friends and parents because I loved it so much.

[00:15:34] It is one of the most gripping open paragraphs of a book I've ever read in my entire life. So I'll commend you on specifically that paragraph, because it was so touching. I was like, man, this is an important book. But just continuing on. So what is it about trauma or hard things or broken parts that allows us to make transcendent art?

[00:16:00] Because it seems to me that you can make good art. Just from putting in the work, you can get in there, put in the hours and make something good that touches people. But to make transcendent art, it seems to have to come from a place of a wound. It has to come from a place of brokenness. Why do you think that is?

[00:16:20] Russ: Yeah. I think about this a lot. I'm a pastor. And so I think a lot about when I'm speaking to my congregation, I'm always pretty mindful that part of the way I'm speaking - part of the way, my words will find them - I can get to the heart through a wound better than I can get to the heart through a clever turn of a phrase. And it was Jesus' encounter with the woman at the well in John 4, that when he was speaking with her, they were having this kind of conversation where she didn't really understand who she was talking to and he raised the issue - he talked about having water that if she drank it, she would never thirst again. And she said I'd love to have some of that water. Can you give it to me? And he said, go and get your husband. And she said I don't have a husband. And that's when Jesus said "I know you've had four" and the man that you're with now, isn't your husband.

[00:17:32] And her guard went down, but he got to her. Because she said, you must be a prophet. And that's when he started to reveal who he was to her, was he got to her through her pain and he got to her through her brokenness. And I think transcendent art is art that tells the truth, in an unapologetic way. People will ask me sometimes, if you're a Christian - Christians will say, how do I make good Christian art? And what one, what my standard response is, don't ever try to make Christian art. Try to make honest art and if you make honest art, the Gospel will be in it. But if you just try to make Christian art, it won't come across as the Christianity of the Bible. It'll come across as something meant to inspire or something idyllic or there are certain painters out there that are known for being Christian painters.

[00:18:31] And it really does very little for me because I think, well, I don't, it feels like part of the agenda here is to paint an idyllic world, but we don't live in an idyllic world. We live in a world where there's a prodigal son whose shoes are falling off of his feet as he's blown through his father's inheritance. And the only place he can go after he reaches the end of himself is back to the father that he disrespected and rebelled against. And the result is he's wrapped up in the father's embrace.

[00:19:06] I think art that tells that kind of story, or that fully acknowledges the brokenness and the ugliness of the world that we live in. It is. Is the kind of art that people will stand in front of and say okay, this is telling me something about myself and this is telling me something true.

[00:19:27] This is helping me navigate this world. So in the book I talk about there's several chapters where the stories that I unpack of these different painters they're not admirable people at all. They're insufferable. Some of them are probably pretty abusive. And I made a commitment early on in writing this book to have no hagiography, which is just a fancy word for a biography of a Saint. Hagiographies are biographies about Saints written to demonstrate why they're Saints.

[00:20:02] So only the good news, right? And and then maybe polishing the good news quite a bit. And I was like, no, I'm gonna, I'm gonna write about art that I connect with. And in the process of writing about it, I'm gonna learn some of their stories. And I'm not gonna try to put a positive spin on anything negative that I see.

[00:20:22] And so it made certain painters like Edward Hopper is one that comes to mind and Caravaggio who their stories are really frustrating because they were not good people , and in the process of not being good people, they created art that speaks to me about the brokenness of the world in a really profound way. Caravaggio in the way that he depicted Biblical truth and Edward Hopper in the way that he depicted loneliness and despair because it was coming from somebody whose life was marked with loneliness and despair and a pretty high level of narcissism. And you see it and it aches his work aches because of it. But we relate to the ache.

[00:21:08] Taylor: Would you mind sharing the story of Caravaggio because that was personally - That chapter affected me greatly, on a personal level. I connected with that on multiple levels and I think it's important. I think it's actually important, especially when you're talking about the creation of Christian art, because one of the most fascinating parts about this thing is a lot of these guys were making the art that is held up now in the Churches as this great art. But the reason that it was connecting to people is it was because it was made by broken people. So it's reflecting the Gospel because they were broken, not the other way around, which is just fascinating. So I wonder if you, if wouldn't mind sharing the story of Caravaggio.

[00:21:55] Russ: Part of the process for writing this book for me was I didn't know all of these stories before I decided to write about them. So for me and this is one of the ways that you can learn to appreciate art is to - when you encounter something that you like, just note that "Hey. That's something I like. I'd like to know more about that" and then go learn more about it. That's what happened with the Caravaggio chapter. When I was a child, I saw painting, a reproduction of his painting, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, which is Jesus and Thomas and two other disciples. And Jesus is putting Thomas's dirty finger into the open wound in his side, after the resurrection. It's that part of the Bible. And as a kid, I remember seeing that painting and feeling like I like I wasn't probably supposed to see that painting because of how grotesque it is. And yet at the same time being really curious about it and drawn to it. And so I knew I wanted to write about Caravaggio and I thought I'll write about The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. I'll write about that painting.

[00:23:04] And then as I started to research, I realized pretty quickly, oh, that's not a major painting for him. And really there's some other paintings that are more centrally known for being Caravaggio. But even with that, I was like, it's really the story of this guy's life that is the story that helps you understand those other paintings.

[00:23:24] And that is the Caravaggio was an extreme picture of a person who embodied both profound corruption and an understanding of transcendent grace. And it came through in his life.

[00:23:41] One of his biographers saying, for Caravaggio, there was only carnival and lent and nothing in between. So Caravaggio was a murderer. He murdered at least two people, maybe three. He spent most of his artistic career trying to evade capture by Roman police who had a death warrant to put him to death because of people that he killed.

[00:24:12] He would get these commissions to paint these alter pieces and he would paint them. And when he was working, he would cloister himself away and it would be just this focus time and he wouldn't be coming out. And then when he'd get his commission, he'd spend a month or two just carousing in the streets and getting in fights and drinking and people would end up dead from these fights that he'd get into.

[00:24:39] And then he'd have to flee that area and they'd go to some other place in Italy and he'd paint for commission and go carousing and get into trouble and have to flee from the law again. And his story is really a sad one. And one of the things I do in the chapter is I juxtapose these tragic - the tragedy of his life and his story with, okay, I'm gonna tell you a terrible stretch of his life and then at the end of that, I'm gonna say during this time he painted, these are the paintings he painted. And then after that, he fled from Rome to Naples. And when he was in Naples, he got into this fight and this, killed this police officer and then had to go on the run. And while that was happening, he painted The Incredulity of Saint Thomas or The Conversion of Saint Matthew or whatever.

[00:25:30] And it was fascinating for me to think through, okay, here's a person who he seems insufferable miserable, lonely, jaded, self-centered, hungry for money, indulgent of any appetite that came his way. And also somebody who, when painting Biblical scenes had this profound insight into the meaning of the ministry of Jesus to broken people, and to sinful people, to doubting people, to people who had a complicated relationship with Christ, and yet also an actual relationship with Christ, like Matthew, the text collector, or Thomas who doubted the Lord.

[00:26:20] And so his life is this is this kind of juxtaposition of while he is living this hard criminal existence, he's also producing these profoundly transcendent, Biblical proclamations of the ministry and faithfulness of Jesus to sinful, and hurting people.

[00:26:45] One of the things I love about that chapter is I don't know anybody who doesn't have some measure of the paradox of corruption and grace living inside of them. We are all that way. Caravaggio happens to be a cartoon version of - a caricature of it. An exaggeration of it in some ways, even though it's a true story. But it raises the question for me of, okay, what can disqualify somebody who seems to have a relationship with Jesus from the grace of Jesus?

[00:27:25] Because here's a person who, you know, when Jesus was talking to Pontius Pilate and Pilate said, "Are you a king?". Jesus says "I'm here to do the will of my father and those who hear my voice know me." And I look at Caravaggio's work. And I think, okay, this seems to be the work of somebody who knows Jesus. Who knows him.

[00:27:52] And Jesus says, "They're mine". And yet Caravaggio's life is this thing that most people would look at and say, there's no way that he was a recipient of the grace of God. And I wrote the chapter to linger on the puzzle of all that and to say, okay, so is there a point where Caravaggio could have behaved a little better and thus been worthy of grace or could he have been even worse and still been kept by the grace of Jesus. Those are high stakes questions for all of us.

[00:28:32] And I'm not a Universalist, by any stretch. I believe in salvation, by grace, through faith in Christ alone. And and yet I think, as a pastor, and just as somebody who lives in the same world as everybody else, I know people and I know tendencies inside my own heart where we have an incredible capacity to hurt each other and to disobey the clear teachings of scripture and yet the Gospel of Jesus Christ, his life, death, and resurrection, on behalf of those who believe, surely, it can't be something that I can - I can't destroy the power of his ability to hold onto me. And so that's - those are a lot of the questions that the Caravaggio chapter raises.

[00:29:24] Taylor: What spoke to me about that chapter was - so behind me we have The Ragamuffin Gospel. When we started Hope, my meditation app. We have a core group of five people that started this thing. And so we met before we started and we said, okay, what do we want this company to be? And that was one of our core, guiding worldviews was I, we wanted to make a Christian product for broken people. And what I loved about this is I am drawn to wild people, who have a wild heart for God. And it seems to me that at least some of the Bible you have Peter. You have David. These are wild men that are bombastic. They're maybe out of control, but God seems to love these passionate wild men. And I see that in Caravaggio. Why do you think that sometimes the wild men are the chosen vessels of God for certain types of truth? What I loved about him was that he was reflecting the heart of the poor people, the broken people, and that's what they connected with. Why do you think God likes these wild men to impart his message?

[00:30:55] Russ: Yeah, I think, let's just rehearse it a little bit, right?

[00:30:59] You have Abraham, who lied about Sarah being his wife, and had a concubine and slept with other women. You have Moses, who murdered the soldier in Pharaoh's army and lied about it. And you have the Jacob, who the thing the main thing we learned about him early on is he was a deceiver and he wrestled with God. David was a murderer and an adulterer. Jonah resented God telling him to go offer the Lord's forgiveness to a race of people that he hated. Hosea was charged with taking a prostitute as his wife and returning to her over, having her return to him over and over again and him never leaving. Peter denied knowing Jesus. Paul wanted to see the Church extinguished and oversaw the stoning death of Steven. Like when you start to do the math and you add it all up, it is compelling to me that part of the message of the Lord in leading his people into truth is to have it come from the mouths of people who have done the unthinkable.

[00:32:29] Because, in that, we have to say it can't be the righteousness of the person that makes them worthy of the love of God. It has to be the righteousness of God that makes a person worthy of His love. It has to be the mercy and the grace of the Lord working through imperfect vessels, in spite of their flaws. It has to be the Lord's work, not ours.

[00:33:00] And so even - so with Caravaggio that's one of the things that I'm reminded of in that is I just think here's the Lord working to make his message known, to make his mercy and grace known to make the compassion of Jesus known through the life of this person who on the one hand has a list of terrible things he's done but on the other hand, it's not that it's not any worse than stuff David did or stuff Moses probably did or Paul. Like it's just a different form of brokenness and recklessness and being adrift in the world and trying to figure out where our security lies and where it comes from.

[00:33:45] I'm encouraged by that deeply. Because when I read the beauty of Psalms, for example, they're written by David, who he was a lot like Caravaggio where he had these this deep affection for the Lord and understanding of his compassion and really saw God as his rescuer, which Caravaggio seemed to do too.

[00:34:12] But he also believed his own press and treated people often or occasionally as being beneath him and his life being more worthy than theirs to carry on and that sort of thing. And so there's something beautifully true about the nature of the mercy of the Lord and how he works through imperfect vessels. So often. All the time.

[00:34:40] Taylor: I love that. You say at one point in the book that, that when we ignore beauty, we're ignoring something essential to God. I think there are a lot of people that would disagree with that. I wonder if you could explain that statement and then maybe address what they would feel is maybe something inconsequential, something extracurricular.

[00:35:07] Russ: Yeah. Yeah. One, I would say if you disagree with that, just examine your own patterns of behavior. Do you listen to music? Do you watch films? Do you read books? Why? Even sports. Sporting events. We're watching to see a team win, but really what we're watching is we're watching for the batter to hit it out of the park. And we're watching for those moments of splendor. We're watching for Jordan to dunk over three people. To have those moments where we say that was the thing of beauty.

[00:35:51] The first thing we learned about God is that he's, or one of the first things we learned is that he's glorious. And that when Moses wanted to see him, God said you can't because the glory will kill you. It's more than you can handle. And if we're serious about really wanting to know God then there are - philosophers call him the three transcendentals - that we pursue the goodness, truth, and beauty. And in the west, we can be very pragmatic. And so we can emphasize or focus on the truth and goodness part. Just tell me what I need to know. Give me information, that I may make an intellectual ascent to truth. Give me application. Tell me what I should go and do, because this is true. So gimme something when I walk out of the Church service. Give me three things to go do this week.

[00:36:46] But when you look at the teachings of Jesus, he didn't teach that way. He didn't teach that way really at all. In fact, he withheld a lot of application. What's the primary way that Jesus taught. It was through storytelling. It was through parables. We have a couple places in the gospels where there are sermons from Jesus. The sermon on the mountain and another place or two here or there. But the vast majority of his teaching is - there was a man who fell among thieves or those sorts of things. He would tell these stories.

[00:37:23] And part of what he's doing is he's not just giving you data and he's not giving you data in order to then say, now apply this data in this way. He's saying to the rich young ruler who asks a very pragmatic question. What must I do to inherit eternal life, which on its surface is a ridiculous question because nobody does anything to inherit, right? We inherit because of who we are in relation to the one who gives - not because we earn it.

[00:37:58] But he says, what must I do to inherit eternal life? And he tells him this story and the rich young ruler walks away sad because Jesus says just give everything away that you've got. And he doesn't - and that's not a teaching that Jesus gives to everybody, but he gives it to this guy.

[00:38:18] Why does he give it to this guy? Because he's saying to this guy, the thing that's keeping you from inheriting eternal life is this insatiable desire that you have to possess everything now. And you have to let that go. You have to count - you are belonging to this world as something that is like a vapor. And it can all go away. I think about that. I think about Jesus' method of teaching and part of what he's doing is he's engaging with the heart and the imagination and he's making us think through the layers of a story. And this all has to do with beauty. Is that part of what beauty is is getting at the layers beneath just data.

[00:39:12] And so it's why lyrics to a song when they're read, it's a very different impact than if you hear them sung. If you hear them in the context of the song. They move you differently. It's the same words, but what's happening is they've been - they've been encased in and delivered in a beautiful way or in a haunting way or in a rhythmic way with crescendo that, that affects us more deeply than just hearing the words themselves.

[00:39:54] But we live this way. Everybody lives this way. Rich Mullins, what was the way he said it? He said he described people as we dress like flowers and we eat like birds and I think, I love that image. As much as pragmatic as we might wanna be, and as outcome oriented as we might wanna approach things and just gimme the applications and the list of things to do. And three steps toward a, whatever.

[00:40:28] The way of God with people, even with Abraham, when God was making his covenant relationship with Abraham, he said, you're gonna be the father of a nation. And Abraham said, my wife and I are barren. How's that even possible? What did the Lord do? He didn't say, I want you to think of the biggest number you can think of. He said, I want you to go look at the desert sky and anybody who's ever looked at a desert sky at night, it's one of the most beautiful things you'll ever see. And it's mystifying and it's cosmic and it's, and it makes you feel so small and so privileged to be in the presence of something so spectacular and asteroids fire across the sky and these little streaks of light. And that's what the Lord told Abraham to look at in order to imagine the nation that he would be the father of.

[00:41:22] And that's how the Lord engages with us. He calls us to engage with and interact with beauty and transcendence as a way of understanding things more deeply than just what the data alone would give.

[00:41:36] Taylor: I think what's hard about this is hindsight is 2020. We look backwards at these artists and we see the totality of their life. We have their story from beginning to finish and you say, wow you, you see the good and the bad, and we can make a judgment on these people as they are. I think what's hard for people is to hold these ideas in their head as they experience them.

[00:42:02] We can take like a modern example, somebody like Kanye West. A man who I think without doubt has a strong desire seeking God, but he's a man with a lot of issues. How do you think modern Christians should think about somebody like that? And not him specifically more just in the general of, we have we have a Christian media that like you said is largely preaching to the choir and is devoid of any of those rough edges that I think people find attractive. But then on the other side, we have rough edges and undeniable genius. And it's this hard, it's this hard thing to hold in your hand.

[00:42:45] Russ: Yeah. I think part of the way I would answer that question is I think maybe we shouldn't think that much about them. Maybe we shouldn't wonder too much about the inner workings of other people's hearts.

[00:43:06] I think we live in a time where we have such access to information. So you and I are talking right now as this is being recorded about three hours after the death of the Queen. I know the Queen died already, right? Because we live in a time where information is global, immediate, and free.

[00:43:31] And so it's hard for people not to know that the Queen is already dead by this point, because it's everywhere. If you open a social media app, or if you look online or if you turn on a TV or, or listen to a radio, get in your car, you're gonna hear it. And I think there is a - there's a passage in the New Testament, I forget which epistle it's in, but basically says aspire to live a quiet life. And I think one of the things that we - one of the things that's hard about living in the era that we're in and especially for young people is we have just so much access to information that we really have no business knowing.

[00:44:15] And we have so much access to information that is so tragic and so weighty, and we have to carry it all around in our hearts in some way or fashion. We know about wars that happen and mudslides and hurricanes and shootings and all these different things. And on the one hand, it's a privilege to be able to know about things that are happening in the world, but I don't think our hearts were meant to carry all of the information that we're assaulted with every day.

[00:44:46] And I think. , I think about somebody like, like Kanye West. I think probably if I were to try to figure him out, one, I would be having to use things I see online about him or that, and some combination of art that he has produced. That's been through a very rigorous production process. And so I'm either getting tabloid-esk information about a person or a very polished and controlled product released by the person.

[00:45:26] But nowhere in that equation, am I getting Kanye West? I'm just getting stories about him told in a particular way. And I think that applies to a lot of things. And I think that's part of the challenge right now of honoring the dignity and the personhood of image bearers of God, is that we really turn each other into cartoons pretty quickly. Or the information we get is so incomplete and so editorialized, and so focused that really we're carrying around such impartial and in incomplete information that it doesn't help us really at all to know the true story of another person.

[00:46:14] That being said I think, I wanna always be careful to say if the information that we get about these people that are being put forth as examples of examples of whatever that, that we wanna, we want to remember that we're not getting anything complete.

[00:46:43] Taylor: It's a tricky spot because it is, I see especially younger people, and I would consider myself part of this. I'll just use me as a personal example. This is a new show for us. When I started this company, I wanted to create audio meditations because I thought it was something that could help people. But I love audio. I love working in audio and part of that was not showing my face. And then my team was like, hey we need to get into video podcasts and this kind of where things are heading is video. It bothers me. I'm not like somebody that loves being in front of a camera.

[00:47:24] And I think the hard part, especially for young people, is that you are looking at these young artists. And part of what you say in your book is that you have to expose your wounds because when you expose your wounds, that's what people connect with

[00:47:39] Russ: Yeah, I talk about Van Gogh's self-portrait with bandaged ear. That one of the things that's - if you know anything about Van Gogh, probably it's that he cut off his ear. Like that's the thing. That's the lead story, right, for Van Gogh is he painted Stary Night and he cut off his ear. And that episode of him cutting off his ear was the lowest, most humiliating point in his life. And that's part of the reason why we know about it.

[00:48:09] But he, when he went into an insane asylum afterwards as part of the recovery process. And while he was recovering, he painted himself twice, with his bandaged side showing. And there's just such a paradox there because when you're painting, you can paint whatever you want. It's not a photograph. He could have painted the other side of his head that didn't have a bandage on it.

[00:48:38] He could have painted his ear intact, even though it wasn't, but instead he painted a picture of himself with his wound showing toward the viewer with the bandage over it.

[00:48:49] And so what I love about that, in fact I'm reaching my hand, I'm touching a framed print of it right now that's in my office. That's right here. I keep it right above my desk because as a pastor, this is what I want to do with my people. Is I want them to be, I want them to see the wounded parts of me because to withhold that is to withhold the need for the Gospel. If my presentation to my congregation is I'm fine, everything's fine.

[00:49:16] I'm just here to minister to you all. I lose the credibility of having a voice in their lives when they suffer. The beauty of and the irony of Van Gigh's self-portrait with bandaged ear is he captured on canvas the most shame filled humiliating point in his life and now it is of incalculable worth that -

[00:49:40] and that's us. We are wounded and we have our areas of brokenness in our lives. And yet at the same time, even as those are seen, because we're made in the image of God, we have inherent dignity and incalculable worth given to us by our maker. And it's unassailable, and yeah, so that's what I was getting at with the letting the wounds be seen as part of it is this, it gets back to this idea of art that's true. That's honest. This is Van Gogh painting something that's honest. He could have painted himself, like Napoleon on a horse, if he wanted to try to give some sense of I'm okay, everything's fine. Instead he owns his own fragility. And when we look at it, we can't look away.

[00:50:32] Taylor: I think what's hard though is I have a camera on me and it's hard to know how much to share. And especially if you're looking at a young artist, they have the social media. I'm not a big social media person, but you have the social media and then and you're talking about to create something that's true and that stands the test of time. You have to be honest and you have to expose these wounds, but we're in this weird spot where Van Gogh had the separation between the painting and he never saw get monetized. We've gotten to a point where we're almost monetizing wounds immediately. Which is very strange.

[00:51:10] Russ: Yeah. And it's yeah. And that's a good point. That's something we have to be really careful with because, we have to question our motives and the appropriateness of how we share. Like I have a pretty subdued relationship with social media. There are a few things I do on social media and other things that a lot of other people I know do on social media that I don't.

[00:51:34] You won't find a lot of pictures of my children on social media. You won't find a lot of, really personal stories on there. And it's not because I don't want people to know me personally, it's that I don't want Twitter to know me personally. Twitter doesn't need to know who I am that much.

[00:51:51] My Church knows a lot more about me than social media does and the small group I'm a part of knows even more than that. And my wife knows it all, and I think it's part of figuring out. Okay. For what purpose are we being transparent with our lives and hearts. If it's for the sake of being known, being encouraging, being part of community, an ongoing relationship with people we're walking through life with, then yes you want those relationships to be ones of gradual and increased disclosure, but if you're just putting yourself out there for the whole world, no holds barred, nothing off limits.

[00:52:34] It's worthy of asking the question. Why? What's the goal here? Is it something - because here's where it gets really twisted is. What if after you do a lot of examination of your own heart, you realize that the goal is I want the world to think that I am this really transparent, honest picture of humility and wisdom. When, in fact, what you're just doing instead of vacation pictures on the beach is you're just curating a different narrative about yourself that may or may not be any more true than the curation of somebody's Instagram that's just them traveling the world. We have so much control over the narrative that we put online, that it's easy for us to come to present something to come across as, wow, this guy he's really deep. He's really smart. He's really - He's really done a lot of work. He's pretty in tune with himself. And really it's no, I just know that these are the things that make people think that. And so I'm gonna give you as much of that as you want and go about my day.

[00:53:44] Taylor: It's very odd. And I'll even expose myself a little further here. So you talk about Van Gogh and you say he had a desire for admiration but an inability to accept it. I think that is true of myself. I try to fight it as best that I can. I think that's true of most artists. And I don't know this. I presume, maybe not for yourself, but for lots of pastors that's true of pastors as well.

[00:54:14] I wonder how you hold these ideas in your head because largely we make the things that we make for the consumption of others. You made this book for the consumption of others. We filmed this podcast for the consumption of others, and it's ultimately to inspire, to entertain, to all these things, but it's made for others. Part of us wants that admiration. And I guess I tend to do my best work when I can leave that. And I think about my desire to do this, to help people get closer to God, but to pretend that those desires don't exist is not true, and it's a hard balance to make things for people and then to hold them at a distance.

[00:54:59] Russ: Yeah. This is all a vanity project. All of these things are in some measure a vanity project. Now not - it doesn't have to be in a gross way. It doesn't make sense for somebody to create something and put it out into the world if they have no desire for it to connect with other people, or it's not something that they feel like they have something valuable to bring.

[00:55:23] But God made us that way. He made us to be people who - one body, many parts is how scripture talks about it. The Psalms talk about often they talk about wanting to grow in our knowledge of the Lord. And part of the ways that we function as human beings is we bring knowledge and experience to other people who don't yet have that knowledge or experience, and they bring the same to us. There are some spheres of influence where we don't think twice about it. We want the doctor to really know a lot about medical things. We want the finance person to really understand how money works, and we want the pastor and the theologian to have had some kind of formal training in Theology and Biblical studies, right? Like those are things that you want.

[00:56:17] I know that there are certain things that I can say from the pulpit that will maybe be helpful, but mostly be said to impress one of the things that we learn in seminaries, we learn how to use Greek and Hebrew, and so as a preacher, on any given Sunday, I could use Greek and Hebrew words and I could talk about them grammatically and I could get into there - and do I have to? No, I could just say in the original Greek, this word means this. That's what I could say, or I could say the Greek word is pronounced this way, and then I could get you to do the and there's a certain point where at least for me as a pastor, I know when I'm flexing. In the pulpit and I don't like the feeling. I know when I'm saying something to get people to think a certain way about me or to garner some sort of respect or something like that. And I think that's a discipline that, that I need to continually want to grow in. And I think we all should. I do have valuable things to bring to the conversation.

[00:57:32] As a pastor, I feel like part of my calling is to serve the local Church, but is also to speak to the Church at large in much the same way that a physician will have it have their practice, but they'll also maybe contribute articles to medical journals. That there's a, that there's a - that I occupy a role in society as a clergyman where part of my sphere, part of my area of influence, and study is things related to religion and theology and scripture.

[00:58:05] And so I'm all about putting things out there into the world that, that are part of that vocational calling. But I think it's a line where we all need the discipline of examining, okay, am I doing this to help add something meaningful to the conversation? And to what degree am I also doing this to inflate people's perceptions of me?

[00:58:29] And I personally, I think if we will, if we're willing to ask the question of ourselves. We probably aren't gonna have that much of a difficult time discerning when and where we're just trying to inflate our own egos and up our own - increase our own popularity as influencers.

[00:58:55] What a weird thing to live in a time of influencers. It says nothing, right? All an influencer is if you're just if the only thing that people know about you is that person's an influencer. All it means is they have lots of people that follow 'em on social media. It doesn't say anything about their qualifications to speak to subjects, a range of subjects. It doesn't say anything about that. It just says, oh, they just have the ear of a lot of people.

[00:59:22] I don't know if that's valuable like when I was thinking about promoting the art book, because we promote - When you write a book you want to get influencers to tell their people about it. And about half the names that I could have put on that list, I didn't, because I just thought this is nowhere near what they do or what their online presence is. It has no I would feel duplicity in even asking them to, to share about my book with the people that they influence. I don't know.

[01:00:06] Taylor: And it is a very odd time to have these people that are wildly famous for no discernible reason.

[01:00:15] Russ: Which is part of the beauty of art, is art has this way of establishing its credibility by just lasting. For example, there's an old anecdote about an art student who goes to the Louvre and sees the Michael, sees the Mona Lisa and he stands and he looks at it for a while and he says to the docent in the room, "I just don't get what the big deal is".

[01:00:51] And the docent says, son, that's the Mona Lisa. The art student doesn't judge the Mona Lisa. The Mona Lisa judges the art student. And I think that's the, that's a fair point that you can't just, walk into the room where Michelangelo's David is standing and say that's terrible because 500 years of human history will tell you, you're wrong.

[01:01:18] Now artist is subjective, but the 500 million people or whoever have gone into that room to stand in front of that statue are telling you that yeah, it's subjective, but there's also something objectively that has happened with this sculpture that ought to humble you in your immediate assessment of whether it's worth anything or not.

[01:01:45] And that's one of the reasons I love writing about art is because I don't have to, I don't have to apologize for devoting an entire chapter to Caravaggio or Van Gogh or Henry Tanner because they don't need me to establish them as some of the world's greatest artists, who have produced some of the world's greatest art. That's already established.

[01:02:07] I get the luxury now of telling you about them. And you can do with that, what you will. But I'm not trying to get anybody to accept them as some of the greatest artists in the world, because. That's already happened. That ship has sailed.

[01:02:22] Taylor: Do you - in your heart of hearts, you believe that art is subjective?

[01:02:28] Russ: Yeah. To a degree. I don't believe it's purely subjective.

[01:02:32] Taylor: Because I guess where I draw that line is you see a lot of, especially postmodern art, is that they say if the art makes you feel something, even if it's disgust or bad, that it is "art". I like Jackson Pollock. I like postmodern - some of that stuff, but some of it. I have to imagine that there has to be some level of, you have to draw the line somewhere. It can't be fully subjective.

[01:03:05] Russ: So a number of years ago, I went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. And as I was making my way through, I was in the room with the Rembrandts, and Caravaggios, the Dutch and Italian Renaissance painters, Vermer. And everybody in the room was quiet, hands behind their backs, looking at paintings. Nobody saying anything to anybody. It's solemn.

[01:03:31] And then I go down the stairs and around the corner and I'm in the room with Picasso and Warhol and Pollock and Rothko and people like that. Everybody's talking. Everybody's talking to strangers. Strangers are talking to each other. And I have a friend who is an art history guy. And I said, what was going on there? Like I noticed this. What was happening?

[01:03:52] And he said you noticed the change in art after the Industrial Revolution. He said the art before that, the Dutch Renaissance people, their art exists to tell you things. They're making statements to you. They're declarative.

[01:04:15] But when you go and you look at some of this modern art, it's interrogative. It's asking questions. It's raising questions. And part of it's purpose is to throw you off. It is to upset you. So you see Warhol who has these silk screens of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis. But then he also had a giant silk screen of Mao, the chairman of China and treated in the exact same way as a pop culture celebrity. And part of what he was trying to say, and this was with the soup cans too, is who gets to decide what's art or not art.

[01:04:58] When he did the soup cans, he was pushing the limit of saying if I as a celebrated artist do a silk screen of a bunch of Campbell soup cans, the world is gonna receive this as a work of art.

Is it? And why would you say that it is or isn't? I think the great thing about museums is there's a little curation that happens.

[01:05:21] I think people can make things and call it art and and we may wonder, is this really art or is this, does this have any kind of meaning at all? But by the time it's been curated to where it's placed in a museum. That tells me anyway that there's something about it that has that has passed a smell test to say it's worthy of being considered.

[01:05:47] And and I think even art that is inflammatory. Art that is things that would offend me as a Christian. Part of the point of it is that I am engaging with a statement that is being made and the way it is being made. And now I'm having to wrestle with, if this upsets me, why? What is it that I disagree with about in this piece of art or what is the question that it's asking that makes me uncomfortable to ask?

[01:06:19] It's a very valid form of art criticism to stand in front of a painting and say, I like this. And it's an equally valid form of art criticism to stand in front of something and say, I don't get this one or I don't like this one. And I think that's part of it but yeah, I'm gonna think about

[01:06:38] Taylor: When I first started getting into art, I was probably middle school, early high school, and I liked early Shepard Fairey, when he was doing all the Andre The Giant OBEY stuff. I liked a lot of David Cho. And I still like David Cho but I think what attracted me to those people, at least at that point in my life, was the attitude. It was almost like a punk rock attitude. You had graffiti artists and they were doing things that they shouldn't have been doing. And that's what attracted me.

[01:07:09] Do you think that ideas and attitudes can be encompassed as - maybe the art doesn't last, but it's the attitude of it? Can that be art? Or does there have to be a level of skill or an objective standard to measure it against?

[01:07:29] Russ: I think about I think about Banksy, the graffiti artist, and I think part of what helps an artist rise to the level of being one that we'll be talking about for generations is not just a thing - a work of art that they make here or there but when you look at the body of work that they've created, what are they saying with the whole of it?

[01:07:58] And we do this musicians with musicians too. Springsteen, Paul Simon. You look at the body of work as a whole, at a certain point. And Banksy is fascinating to me because he's unknown. He doesn't show his face. He's a graffiti artist. He shows up all over the world. His work shows up all over the world.

[01:08:23] I do a series on Wednesdays called Art Wednesday where on my social media. Post Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. I devote the entire day to posting a series of painting that are either all by the same artist or connected in some way. And coming up, I have a focus on Banksy and his work.

[01:08:46] And I have these different pictures of murals. Graffiti murals that he's done around the world. But he has this very famous image of a little girl holding a heart shape balloon. There was a painting, a copy of it, that was framed by Banksy that was being sold at this at a Sotheby's auction. And and it went for, over a million dollars. And when the gavel went down, after the highest bidder bought the painting, the frame started to vibrate. And the picture inside the frame started to come out the bottom of the painting through a paper shredder. And what Banksy had done is he had built a paper shredder that was remote control operated into the frame so that he could sell this image that he was famous for, but his images were all about the horrors of capitalism. Somebody spends and a gross amount of money to him on this painting and after they've purchased it, the frame that he put it in devours it, and it's just it was this beautiful like moment of art artistic genius.

[01:10:08] And it the shredder bound up when it was ha almost halfway through shredding the paper. And so half, about a third of it was still in the frame and the other two thirds of it were just hanging out the bottom of the frame there. And and then of course, the art community said, now it's worth double what it was before the person bought it, because it's now it's performance art, but I look at stuff like that, and I think whether you agree or disagree with the overall message of what he's trying to say, he's using art to come at it in as many different ways as he possibly can to keep saying the same thing. We're not made for war, capitalism will destroy your soul, if you let it, innocence is being stolen from children because of our use of money and our use of weapons. Things like this that are part of what he what is his overall message. And I find that Sotheby's auction should - just what a moment. You can watch it on YouTube. You can watch it actually happen on YouTube.

[01:11:20] Taylor: Oh, really? I love Banksy. Just watching the time here, would you mind sharing the story of the Rembrandt painting being stolen? That was a totally new story to me and I think a lot of people will find that very entertaining.

[01:11:38] Russ: This story is really the impetus behind the book. So this was the first chapter that I wrote for the book. And I really wrote it as an essay to be delivered at a lecture as a lecture at a conference.

[01:11:48] And it's the story of Rembrandt painting the storm on the sea of Galilee, which is one of it's my favorite Rembrandt painting. And and in 1990 on St. Patrick's in Boston. So St. Patty's day in Boston. That painting was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum, along with 12 other priceless works of art, including a Vermeer, a couple of Degas, and some Manets and they haven't been seen since.

[01:12:19] So that was 1990. That's 32 years ago or something. There's a 5 million bond on the on - reward for their return. Nothing. They've gotten it and they've gotten nothing. That particular painting is a large scale painting. And the thieves, who dressed up as Boston police officers to gain access to the museum at night, they got the guards to buzz them in and then they tied up the guards and put 'em in the basement and spent the night taking art out of the museum.

[01:12:53] To get that particular painting out, they cut it out of the frame with a box knife and Isabella Stewart Gardner, the woman who made that museum, that was her personal collection of art that she and her husband had collected. And she designed this museum, after her husband died, as a way of trying to preserve something that would last. And one of the stipulations, that she put in the trust for that museum, was that the collection could never change that you couldn't add to it and you couldn't take from it. And if you did, then the whole thing would have to be liquidated and given to Harvard. Harvard university. And so when that painting was cut out of its frame, because of that rule, they couldn't take the frame off the wall. And so if you go to the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum in Boston today, you can go into the room where that painting was cut out of its frame and the frame is still there. It's still there on the wall.

[01:13:53] And what fascinates me so much is the subject matter of that painting. Is the disciples in the boat with Jesus in the storm, and Jesus is sleeping. And they're frantically trying to wake him up to ask him the question. And the question that they ask him is don't you care that we're perishing here? And Rembrandt painted himself into that painting as the 13th disciple, and he's in the middle of the boat and he's looking out at the viewer.

[01:14:20] And so at some point, there's this thief dressed as a police officer with a box knife, eye to eye, with Rembrandt, as he's cutting him out of the frame, and rebrand is asking him, don't you care that we live in a world like this? Don't you care that we live in a world where things are consumed in terrible ways and that we're perishing here? Doesn't it matter to you? And I just found that to be such a poignant thing that Rembrandt is asking us the question as the disciples are asking Jesus, that question, and he would've been nose to nose with that thief, as he's cutting that painting out of that.

[01:15:05] And I don't know if the thief knew the story of that Bible passage or not. But it's fascinating to think about how the irony of what that painting - the message of that painting and what those thieves did to it. It's a heartbreaking story. And it's been 32 years now.

[01:15:30] My suspicion is that it's been destroyed because, people don't leave money on the table for that long. And if anybody knows about it and there's $5 million to get as a reward for its return, something would've happened by now. And that's my feeling about it. I don't know. I hope I'm wrong. I doubt that I'm wrong, but I hope that I'm wrong on that.

[01:15:56] But yeah, that's the story behind that painting is the museum itself was meant to be something that would last and these thieves came in, they broke it and stole. And now it's not what it was. And and it's, there's a lot of the human condition just in that story alone.

[01:16:20] Taylor: Yeah. I hope you're wrong as well. It's a beautiful painting. I know we are out at time here and I'll ask you one final question and you can answer this in whatever capacity that you feel comfortable answering. You can kind of sense when somebody is writing something personal. This book to me reads as something personal. The way that you write about pain and brokenness, this feels while you're writing about other people's stories, this feels like your story in a way. I wonder if you would feel comfortable sharing, is this writing about pain and brokenness, a personal thing to you? And then I guess maybe how does that bleed into the book itself? Because it's a beautiful book, but it reads to me as somebody that is, that knows something, that somebody who has been there,

[01:17:26] Russ: Yes it's of course it's very autobiographical in, in a lot of ways. It's about more than pain. It is about a, maybe I would say it this way. It's about a lifelong relationship with art and the way that art has helped me in seasons of suffering and the way that art helped me in general, when it comes to the brokenness of this world. That it's a counterpoint to the ugly. It's a counterpoint to the perishing.

[01:18:01] That art is something that is, even though there will come a day when, Van Gogh's work will decay. It hasn't yet and it won't for a long time. I've been through suffering. I've suffered personal things, medical things, relational things. I've lost people.

[01:18:31] I've also by nature of just the life that I've lived and the work that I do, I've had lots of opportunity to see people walk through seasons of great suffering and come out on the other side having grown, having matured. Gaining insights into what it means to be human and what it means to have need in ways that have profoundly helped. As a pastor, when I stand up on Sunday morning and I look out into the congregation, I've been with this congregation now almost four years, and there's so many stories that I know of. People's sorrows and pains of rebellious children and struggling marriages and medical diagnoses and job questions and miscarriages and childhood trauma and things like this.

[01:19:35] And I think, it's a sacred thing to know those stories. It's a sacred thing to have the privilege of walking with people in those stories. And I think one of the things that I love about the power of art is I think art comforts the afflicted. It has a way of saying things that are true and meaningful to people. That we carry around with us in our hearts and in our minds and our imaginations, as we remember, and art has always been a a great comfort to me because of the way that it, so much of it anyway, speaks truth into the struggle. Whether it's on the canvas or in the life of the person who put it there.

[01:20:39] I appreciate you. You've definitely helped me. I have the book here. Rembrandt is in the wind. Everybody should go check it out. Honestly, it is not just for art lovers. It is for anybody that wants to see the world differently. I genuinely, genuinely recommend it. I always - my dad, when he buys books, he highlights like every word and it drives me nuts. And I always tell him, like, why are you highlighting so much, but in your book, you can see on this one page, I underlined almost everything written. That's just a random page that I opened to. It's an amazing book. Russ, you're a great writer and I appreciate you coming on the program and podcast.

[01:21:19] Thank you very much, Taylor. I appreciate.

[01:21:22] If you like to check out Russ's book, Rembrandt Is In The Wind, we're gonna link to it in the show notes. If you wanna learn more about Russ and his other books, you can check out his website, russ-ramsey.com or you can go and follow him on Instagram at @russramsey1.

[01:21:38] I actually recommend that you guys go check him out on Instagram. He does these like mini art stories, where if you like today's episodes, he'll put up a piece of art and he'll tell you the history of the piece of art. And it's a lot of fun to learn these new things. And it's an extension of the talk we had today.

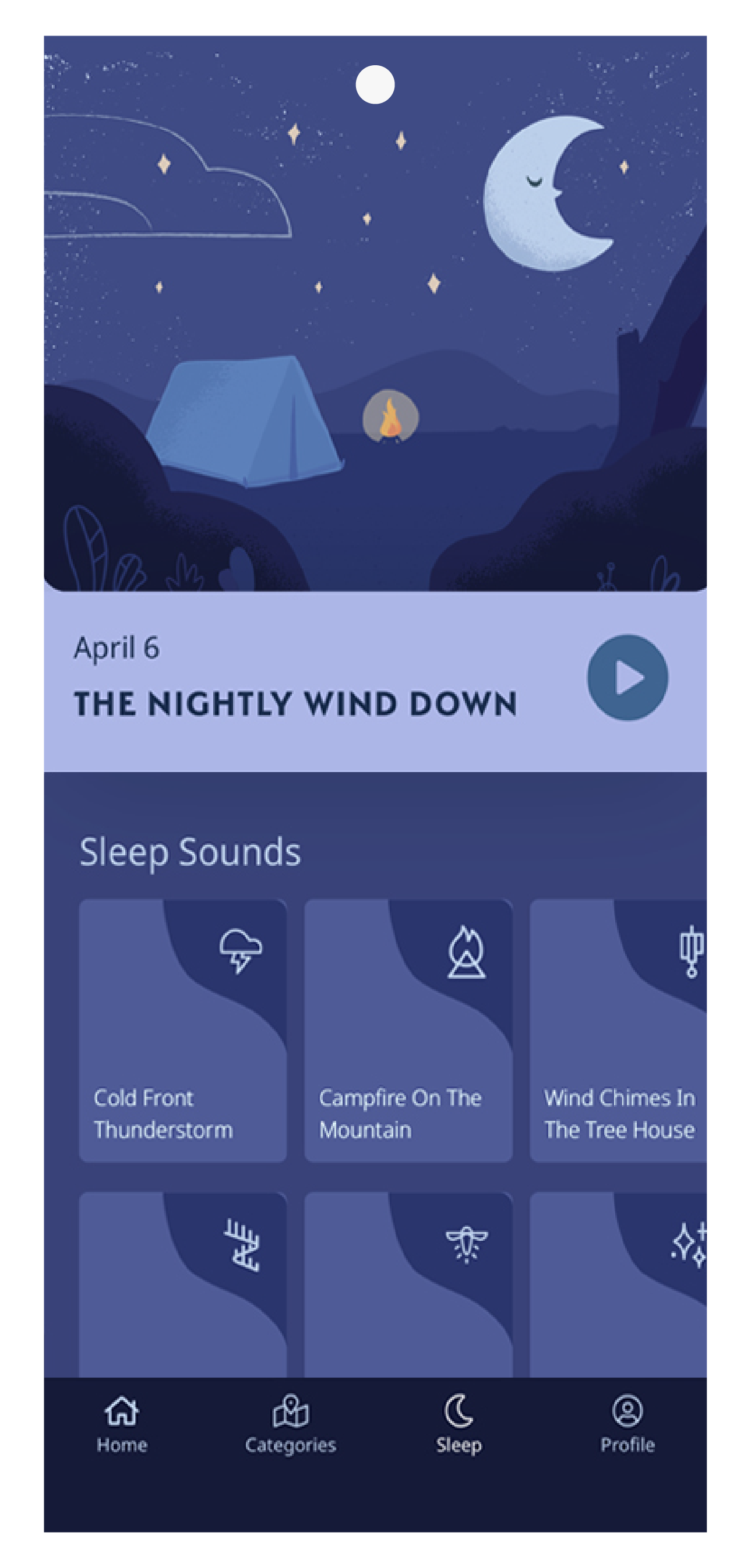

[01:21:53] If you wanna support this podcast, you can subscribe here or you can go and check out our mobile app, Hope Mindfulness & Prayer, which is available in the Apple and Google Play app stores. Thanks.

According to your Purpose

According to your Purpose is a podcast for seekers who desire to live a life of intention. We search out and find the most creative and innovative voices bringing God’s truth to light, in a meaningful and honest way, and bring them to you! Whether it is a creative venture, scientific discovery, physical fitness, mental health, personal growth, or stories of purpose, commitment, connection, or truth, we are fascinated by it all and we want to share that knowledge with you!

ATYP is hosted by Taylor McMahon and produced by Hope Mindfulness and Prayer, the Christian wellness mobile app.

Share:

Christian Meditation

Made Simple